Cooking and Pasteurizing for Safer Foods

We cook food to enhance palatability, flavor, and texture, but mainly to make it safe to eat. Many raw foods contain pathogens that can make us sick. Most cookbooks do discuss the time and temperature necessary to cook food, but usually do not address it as food safety. Too much cooking or too much time (or both) overcooks food such as meat, fish, or poultry. When you overcook meat for example, the fibrous proteins in it become solid, dense, and dry. Other foods become mush. We need a happy compromise between getting the food cooked, keeping it nutritional, moist, tender and safe.

Pasteur’s contribution –Thanks to early scientists such as Louis Pasteur, the human race learned in 1862 about heating foods to kill natural pathogens and retard spoilage organisms that can make us sick. Pasteur is known for developing the method to “pasteurize” milk and wine so it would not sour or turn rancid, not to mention solving other bacteriological mysteries. He combined lower heating temperatures and longer times at that temperature to accomplish a food safety factor without boiling. Before milk was routinely pasteurized, it spread tuberculosis, brucellosis, typhoid fever, diphtheria, and scarlet fever. Pasteurized milk made its debut in the USA in the 1880’s, but took 30+ years (1920) to gain full acceptance.

Pasteur’s contribution –Thanks to early scientists such as Louis Pasteur, the human race learned in 1862 about heating foods to kill natural pathogens and retard spoilage organisms that can make us sick. Pasteur is known for developing the method to “pasteurize” milk and wine so it would not sour or turn rancid, not to mention solving other bacteriological mysteries. He combined lower heating temperatures and longer times at that temperature to accomplish a food safety factor without boiling. Before milk was routinely pasteurized, it spread tuberculosis, brucellosis, typhoid fever, diphtheria, and scarlet fever. Pasteurized milk made its debut in the USA in the 1880’s, but took 30+ years (1920) to gain full acceptance.

Pasteurization is kind of a compromise. If you boil a food, you can kill all bacteria and make the food sterile, but you often significantly affect the taste and nutritional value of the food. When you pasteurize a food, what you are doing is heating it to a high enough temperature to kill certain (but not all) bacteria and to disable certain enzymes, and in return you are minimizing the effects on taste as much as you can. Milk can be pasteurized by heating to 145 degrees F (62.8 degrees C) for half an hour or 161 degrees F (72 degrees C) for 15 seconds. Other combinations of time and temperature can do the same thing, just like when we cook foods. One key point– some foods that are time and temperature abused to start with allowing toxin creation (such as staph aureus) in food may not inactivate the toxin at pasteurization temperatures although it kills the bacteria.

Other pasteurized foods–Milk and dairy products are not the only pasteurized food product available these days. In the mid-1990’s, there were several high-publicity foodborne illness outbreaks traced back to un-pasteurized juice. Now, 98% of all juices in the United States are pasteurized. Eggs are another product that has benefited from pasteurization. Estimates say that Salmonella enteritidis infects only one in 20,000 eggs. With a production rate of almost 60 billion eggs per year, that still leaves close to 3 million infected eggs. Egg products, removed from the shell (liquid, frozen, or dry) must be pasteurized by law. Intact shell eggs can now be “cold pasteurized” with a combination of warm water bath and hot air treatment under low temperatures and longer times so the yolk and white do not solidify. Pasteurized in the shell eggs are required (FDA Food Code) in high risk population food service such as healthcare. Visit SafeEggs for more information on pasteurizing eggs.

Food irradiation is another form of cold pasteurization—It exposes food to very high-energy, short-length invisible waves. Depending on the dose, irradiation performs different functions. Low doses delay ripening and sprouting in fresh fruits and vegetables, and controls insects and parasites in foods. Medium doses extend the shelf life of foods and reduce both spoilage and pathogenic microorganisms so they cannot survive or multiply. High doses disinfect certain food ingredients, such as spices, and sterilize meat, poultry, seafood, and prepared foods.

Although 40 countries permit irradiation and experts confirm it’s a  safe process, the start-up and usage costs for food manufacturers, coupled with the consumer acceptance issue makes progress slow. Remember the previous point of how long it took people to accept pasteurized milk (30+ years). Consumers are becoming educated that irradiation is safe. Recent outbreaks from low dose foodborne organisms (Listeria, E.coli 0157:H7, etc.) are creating more demand and irradiated foods do retain the texture, color, and taste better than foods preserved by heat treatments.

safe process, the start-up and usage costs for food manufacturers, coupled with the consumer acceptance issue makes progress slow. Remember the previous point of how long it took people to accept pasteurized milk (30+ years). Consumers are becoming educated that irradiation is safe. Recent outbreaks from low dose foodborne organisms (Listeria, E.coli 0157:H7, etc.) are creating more demand and irradiated foods do retain the texture, color, and taste better than foods preserved by heat treatments.

Cooking, to be effective in eliminating pathogens, must be adjusted for factors such as: (1) the level of pathogenic bacteria in the food (i.e. poultry is known to have greater numbers and varieties of pathogens than other raw animal foods) ; (2) the initial temperature of the food (frozen, refrigerated or temperature at that stage of processing); (3) the food’s bulk, thickness, or volume which affects the time to achieve the needed internal product temperature. Fat content in food reduces the ability of heat to kill pathogens, but high moisture content in the cooking container increases the kill rate.

Another cooking factor to be considered include post-cooking heat rise. Meats will continue to cook after you remove them from the heat — small cuts like pork chops and hamburgers will rise an additional 5°, while large roasts will rise 10° or so — so the cook might be able remove them shortly before they reach the desired temperature. Heating a large roast too quickly with a high oven temperature may char or dry the outside surface, creating a layer of insulation that shields the inside form efficient heat penetration.

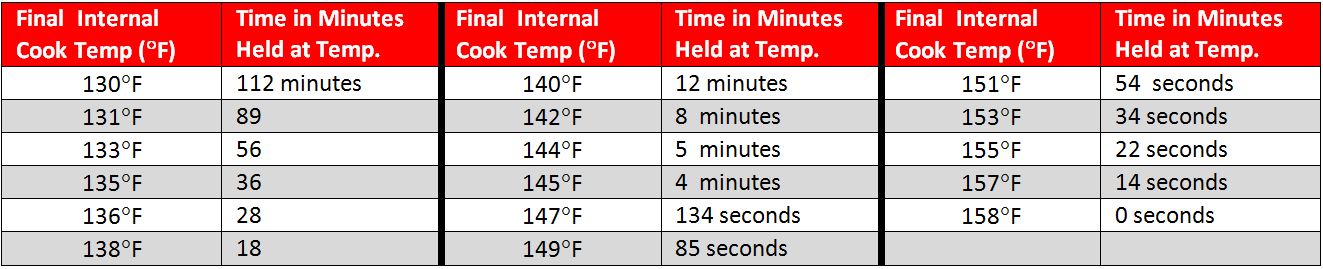

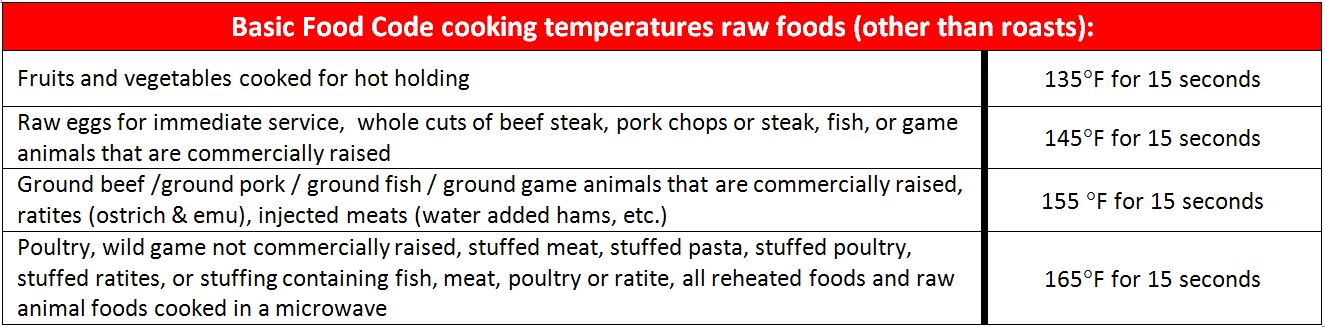

The FDA Food Code contains a minimum safety chart to show the time and temperature relationship for cooking whole meat roasts (beef, corned beef, lamb, pork, and cured pork such as hams). Other basic minimum cooking temperatures are in the second chart and more can be found at the FDA Food Code website / Chapter 3-401.11:

Bottom Line: This information helps us understand how culinary cooking methods and food safety have a delicate balance to co-exist. When cooking, don’t forget to check the internal temperature of the food with a calibrated, sanitized stem thermometer.

***

About the Author: Lacie Thrall

READ MORE POSTS

Meet the Food Safety Leadership Team

Meet FoodHandler's Food Safety Leadership Team:

Announcement from FoodHandler’s Sales Manager

We are pleased to announce that our new food safety consultants—Dr. Jeannie Sneed and Dr. Cathy Strohbehn—will be writing blogs twice each month, on the first and fifteenth. Their goal is to make these blogs relevant, and to continue conversations about food safety among foodservice operators. We invite you to contact them to ask questions, share success stories, make suggestions for blog topics, or provide other thoughts you have about food safety. You can email them at foodsafety@foodhandler.com

FDA has released the newest version of the Food Code

Blog by Lori Stephens based on the new FDA Food Code release.

Stocking Your Food Safety Toolbox

Blog by Lori Stephens, based directly on SafeBites webinar by Dr. Jeannie Sneed, PhD, February 2018