Taking Care of Business through Employee Productivity

In the first blog for May on the topic of Workplace Productivity, we covered some indicators that could be used to track performance effectiveness. This blog discusses strategies to maximize performances of the workforce – because we all know that a foodservice is dependent on staff to meet an organization’s goals.

Helping staff “work smarter, not harder” can improve overall efficiency of labor inputs and lead to better quality, safer food. All of us can identify someone who gets in a tizzy when the work pace increases. This is the person who is always in reactive mode rather than being proactive with planning tasks. You know, the person who makes multiple trips to the storeroom for supplies rather than gathering their thoughts and identifying everything needed with one trip. Chefs call this mise en place, or everything in its place. It requires creating a plan or list, and then executing the plan. For some tasks, the steps become routine. At Iowa State, we received federal funding to find out why front line staff didn’t practice their food safety knowledge and create resources to address the gap. We found that often staff couldn’t find supplies or were too busy to follow basic food safety practices, like washing their hands between handling soiled dishware and preparing foods. It was very clear that a lack of organization was leading to some risky behaviors. So, we created an online toolkit called Do Your PART (Plan, Act, Routine, and Think) with videos, exercises, and a short assessment. Other resources to assist with planning and development of mise en place are available from the North Carolina K-12 Culinary Institute and the Institute for Child Nutrition (www.theicn.org). These sites also have visuals to help staff incorporate time-motion economy principles. Celebrity Chefs call these Hacks, but really the tips for making work simple are based on use of time-motion economy, ergonomics, and work-simplification techniques.

You may have read the book or seen the movie called Cheaper by the Dozen, which was based on the family of Frank and Lillian Gilbreth, who pioneered time motion economy and the use of work simplification techniques. For example, Mr. Gilbreth found it took two seconds less to button shirts from the bottom up rather than top down. In recent years, the important focus on ergonomics has helped in reduction of injuries due to repetitive work motions through thoughtful design of tools and works stations.

In food preparation, we can use some of the techniques in setting up work stations. See some visual examples from North Carolina and a video from the Do Your PART shows set up for assembly of sandwiches. A tray line approach can be used if several staff members are available, each with a dedicated task. For instance, one could be the “linebacker” or the person who retrieves needed supplies and places prepared trays or pans of sandwiches into the cooler while another focuses on adding one or two ingredients. But if only one person is tasked with making the sandwiches, placing needed ingredients in a semi-circle within easy reach allows for fewer wasted motions. With these set-ups, managers can coach staff on how to maximize their labor inputs. In the videos, you see staff using both hands as they assemble the sandwiches, rather than one hand being idle.

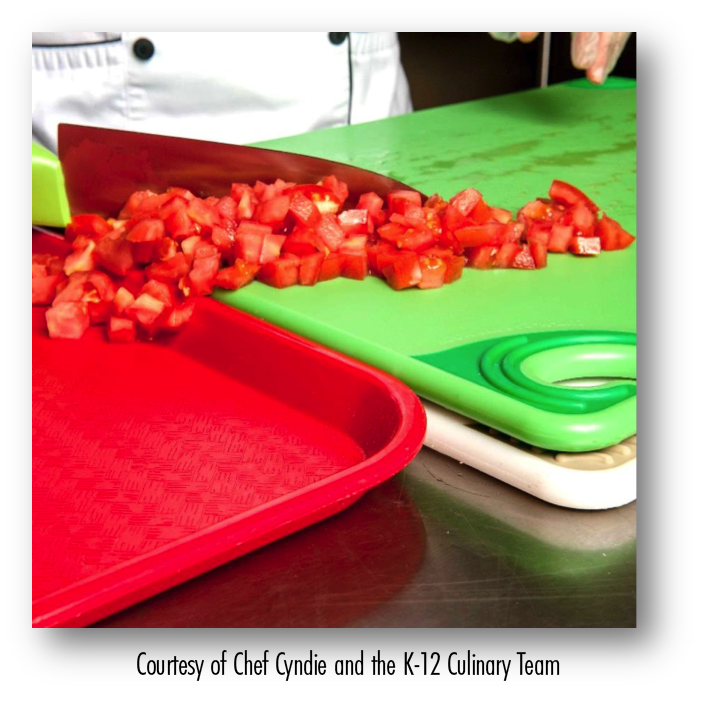

Similarly, gravity for “drop delivery” of items from a cutting board into a pan avoids unnecessary inputs and saves time. Adjustment of work table heights can be accomplished by stacking cutting boards (with wet towel in between to avoid slippage of boards, and potential for cuts) for the taller employee, or use of adjustable mobile carts for those of smaller stature. Our friend Chef Cyndie Story calls this the “chop and drop” approach (see photo below).

One of our former students, Julie Boettger (who is our webinar speaker in October), held a contest with her staff at the school district to see whether portioning applesauce into small serving dishes with a scoop (as advocated by one employee) was more efficient and effective (measures were the time to set up and complete task, as well as product waste) than pouring from a pitcher, which was the approach favored by another worker. They found, for their school, that pouring took less time, and had less mess, not to mention less risk of injury due to repetitive hand motions. Ask staff for their input on what may be ways to improve efficiency and effectiveness in productivity in your operations. Maybe relocation where certain items or supplies are stored would reduce the number of steps needed to access. For instance, research has found that making handwashing stations readily accessible and fully stocked leads to improved handwashing behaviors. As managers, your goal is to facilitate operations – including providing the necessary tools and supplies within a workable environment.

Assess your work environment to see whether the addition of equipment items, such as an under-counter refrigeration unit or a cart, or modifications to work area set up, such as rubber floor mats, could reduce employee fatigue, potential risks for short cuts leading to foodborne illness or worker injury, and turnover, as well as improve efficiencies in operations. We have touched on a few strategies for consideration in your operations. There is a lot more information out there. The bottom line is that productivity requires mindful behaviors, similar to the practice of safe food handling. Operations need to focus on both.

Risk Nothing!