Mitigation Strategies for Cross Contamination

In our last blog, we talked about cross contamination, including the related risks and sources. Our focus today will be on some of the major strategies that can be used to mitigate cross contamination in a foodservice operation.

Before we talk about those strategies, it is important to discuss the role of the management staff in controlling cross contamination. Owners and managers play a key role in food handling behaviors that occur in any foodservice operation. They are the ones who develop food safety policies, procedures, and expectations; provide training; and supervise employees on a daily basis. Each of these functions, which is part of providing active managerial control, will make the difference between a strong, or a weak, food safety program.

Now, let’s talk about some of the general areas for mitigating cross contamination. Some of these strategies you likely are already using, but you may want to check whether the current practices are truly effective.

Handwashing

Because hand-to-food is one of the main causes of cross contamination, handwashing is one of the most important behaviors to control for cross contamination. The guidelines for handwashing state that hands need to be washed between tasks, that they must be washed with warm water and soap with lathering for 10-15 seconds, and dried with a disposable towel. Proper handwashing takes a total of about 20 seconds. To prevent recontamination of hands, a disposable towel should be used to turn off the water faucets if needed. Observational research in a variety of types of foodservice operations has shown that neither the frequency nor the technique used for handwashing is adequate. Managers need to stress the importance of handwashing and monitor to make sure that it occurs properly. While you can’t watch everyone all the time, checking handwashing supplies and empowering peer staff to encourage proper handwashing are other ways to monitor handwashing in the operation. Managers also should serve as role models—never step into the kitchen without washing your hands!

Glove Use

Gloves are required by most jurisdictional food codes when handling any ready-to-eat foods because they provide an additional barrier between hands and food. But just like handwashing, there are some important guidelines for wearing gloves. First, hands need to be washed properly before putting on gloves. Gloves are NOT a replacement for handwashing. Second, gloves need to be changed between tasks. Sometimes I worry that employees forget that the function of gloves is to protect the food, not the employee! So, supervisors need to train staff and then supervise to make sure gloves serve ther intended purpose, and are changed as needed.

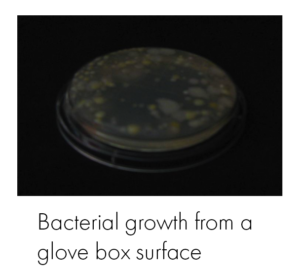

Another thing to keep in mind about glove use is contamination of the glove. Below is a picture of a bacterial growth on the outside of a glove box kept in cook’s area of a production kitchen. Think about it—those glove boxes are sitting out on the counter with cooks grabbing gloves throughout the day. Because gloves are packed with the clean side out, unclean hands digging into the box for gloves will contaminate the others. This picture provides good evidence that perhaps handwashing is not occurring prior to glove use. Another real life example that colleagues observed in a commercial kitchen was a cook knocking the glove box off into a trash can, then picking it up and returning it to the counter! Those kinds of things may be occurring when you are not watching!

*Photo courtesy of Iowa State University Extension Service

FoodHandler offers a glove dispensing product called oneSAFE, that dispenses gloves one at a time from a dispenser. This eliminates contamination from glove to glove and also eliminates pulling out several gloves at a time and the tendency to put them back into the box. oneSAFE has two dispensers, one that is wall mounted and one for the counter. The countertop model has suction cups on the bottom so that it can’t be easily knocked off the counter but it can be moved as needed. This is one option to reduce cross contamination.

Organization of Work and Work Areas

Organizing work and the work area is another important strategy for mitigating cross contamination. You may have heard the French term, mise en place, which means literally “setting in place”. In a foodservice operation we refer to mise en place as getting out the equipment and food that are needed to prepare a recipe. If everything you need is on the work table, then you won’t have to make multiple trips to retrieve what you need and you will reduce opportunities for cross contamination (and staff will be less tired if they can reduce steps in the work day). Remember, you must wash your hands and change gloves between tasks. So, if you are chopping onions and you realize you don’t have enough for your recipe, then off you go to the storeroom and retrieve more. At that point, you would need to take off your gloves and wash your hands. Planning and being organized can help with productivity and food safety. As I learned a long time ago—work smart, not hard!

Cleaning and Sanitizing

Cleaning and sanitizing is another key mitigation strategy. Your first reaction is probably, well we already to that! There is no doubt that cleaning and sanitizing occurs in all foodservice operations, but is sanitizing done properly? We have been in many operations where the dishmachine was not functioning properly—no or inadequate chemicals, temperature too low, etc. Do you have processes to check the effectiveness of sanitizing in your operation? Is the sanitizing solution in sanitizer buckets changed when needed? Are employees checking the concentration of the sanitizing solution in the sanitizer buckets? Remember, sanitizers lose strength over time and if food particles are present. But too much sanitizer is not a good thing, so train staff to use the correct test strip for the sanitizing agent in your operations regularly.

Another area of concern for cross contamination is the dish area. A common arrangement for many foodservice operations is to schedule one person in the dish area with that person loading dirty dishes and unloading clean dishes, often without washing hands between. Can you identify some potential risks for cross-contamination? Scheduling two people so that there are designated responsibilities with one person handling soiled dishware and another clean, especially during busy times of service, can minimize risks of a foodborne illness.

Preventing cross contamination is very important in mitigating foodborne illness. I hope this blog has provided you with some food for thought, given you some ideas on areas that you might want to revisit in your operation, and suggested some strategies that you can adopt or adapt in your operation. Safe food is always our goal! So, join us in crossing out cross contamination!

Please email us questions or comments to foodsafety@foodhandler.com

READ MORE POSTS

Quat Binding – Why this Can Have a Disastrous Impact on Your Sanitation Program.

In June, I had the opportunity to represent FoodHandler and speak on food safety behavior for customers of Martin Bros. Distributing in Waterloo, Iowa. One of the questions that was asked caught me a little off guard. The question was about quat binding. It caught me off guard not because it was a bad question, but only because it was not something I had previously been asked nor had not yet been exposed to the phenomenon. However, I soon learned that in certain jurisdictions, it is resulting in changes to how sanitizing cloths are to be stored in sanitizing buckets (or not) in the foodservice industry. When I returned home from the trip, I had to dig into it to learn about what quat binding is and how it might impact foodservice operations.

Are Grades for Foodservice Inspections a Good Idea?

I generally try to stay away from controversial topics in my blog, but this is one I thought it might be interesting to discuss. Occasionally on my travels, I will come across a state or a local jurisdiction that requires foodservice inspection scores be posted in the window of the establishment. The idea is to allow would-be customers the ability to see how the foodservice operation in which they are about to eat scored on their latest health inspection.

Neglected Safety: CDC Report Casts Doubts on the Ability of the Foodservice Industry to Ensure Ill Workers Stay at Home

Early in June, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a report outlining foodborne illness outbreaks in retail foodservice establishments. The report outlined outbreaks from 25 state and local health departments from 2017 through 2019.

Keeping Food Safe While Serving Outdoors

This afternoon I met some friends for lunch and as I drove through our beautiful downtown area in Manhattan, KS, I noticed that many people were taking advantage of the gorgeous weather and dining outside with friends. For our local community - outdoor dining is one of the remnants of COVID that we actually have come to enjoy on beautiful days. With spring in full swing and summer just around the corner, many foodservice operations are taking advantage of the warm weather by offering outdoor dining options.